Bloodthirsty plants of SA: Sundew, the sweetly-named plant with a sinister secret!

A flytrap cousin of Venus

Drosera is taken from the Greek droseros, meaning dewy. It refers to glistening droplets on the leaves of plants in the Droceracea family. This is the same family as the world’s best-known carnivorous plant, the Venus’ flytrap (Dionaea muscipula, not a native of Australia).

Carnivorous plants tend to grow where soil nutrients are scarce, capturing insects to use as a nutritional supplement – nature’s multivitamins and minerals!

How does a sundew trap insects?

Sundews produce sticky ‘dew’ from glands at the tip of fine hairs. The nectar-like dew is attractive to insects who seek a sweet meal, but they become trapped in the sticky goo.

Some of our sundews have ‘trigger’ hairs that flick the insect into the centre of the leaf. More hairs move inwards to wrap around the insect, and in some cases the whole leaf curls over too.

The dew contains enzymes which break down the insect so its nutrients can be absorbed by the leaf’s surface.

Four types of sundew to find in South Australia

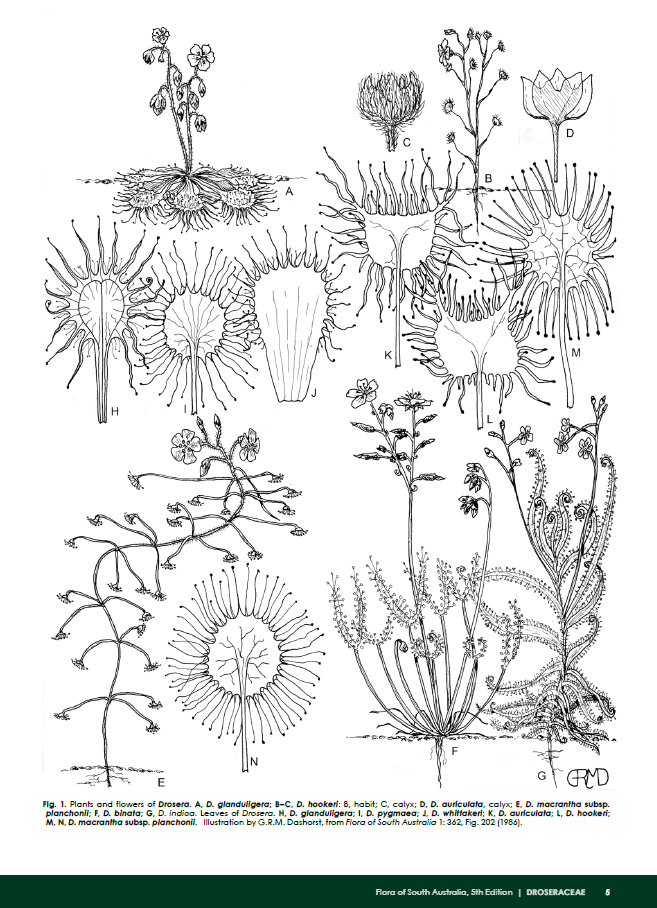

Around 17 different species of sundews are currently recognised in South Australia, with some unique to our state. They take four different main forms:

- Low rosettes of rounded leaves, which may be green or have a deep reddish tint.

- Climbing sundews with small, cupped leaves dispersed over delicate, long branching stems.

- Longer, thinner leaves with an upright growth habit.

- The forked sundew whose long, thin leaves fork into two or more parts, each covered all around with fine, dew-tipped hairs.

Where and when can I find sundews?

Sundews are common amongst native vegetation in the Mount Lofty Ranges, Fleurieu Peninsula, Kangaroo Island and areas of South Australia’s south east.

Look for them from late autumn through to early spring.

The small, tuberous rosette-shaped sundews are usually the first to appear and flower, in the understorey of woodlands and around the edges of wetter areas.

You might spot them on the edges of walking paths, where they can form little dewy clusters.

In arid areas of South Australia, sundews can pop up at the edges of creeks, lakes and waterholes after seasonal rains and floodwaters.

Once you start noticing sundews, you’ll become familiar with the types of areas and conditions they like.

As with a lot of Australia’s fascinating flora, they’re small and subtle, but well worth seeking out.

How do sundews reproduce?

(If that’s not too personal a question!) Many of our local sundews are tuberous perennials, meaning they regrow each year from an underground tuber; a kind of thickened stem that stores nutrients and energy while the plant is dormant.

After flowering and setting seed, the plant forms another tuber, so it can increase its family cluster as well as spreading its seed.

Others grow new plants just from seed. Sundews in more arid areas prefer this kind of reproduction, because seeds can sit dry and dormant for a few years before the conditions are right to germinate again.

Can I grow sundews at home?

Firstly – it may seem obvious – but don’t take any sundews that you find growing in the wild. For more about native plant laws and permits, have a look here: Department for Environment and Water — Collect native plant material .

You may be able to find sundews or seeds sold by specialist plant nurseries and collectors.

To mimic a sundew’s natural environment you will need a low-nutrient growing medium, and a constant supply of rainwater or other source of low-mineral water.

Depending on the variety it will grow as an annual and die off completely, or need a dormant season each year.

And of course, a sundew will want access to tiny living bugs as food.

Sound a bit fussy? In general, unless you have a really green thumb and lots of enthusiasm, it’s best to simply enjoy sundews where you find them.

The sundew bug

South Australia’s own State Herbarium has been involved in a number of recent studies involving our fascinating sundews.

One has been a study of the sundew bug, in collaboration with entomologist Dr Gerry Cassis.

The bug (Setocoris) has the ability to walk on sundew leaves without getting stuck, and helps itself to a meal of other bugs that are trapped.

Is it simply stealing from sundews?

In fact, it might be helping by pre-digesting and leaving its droppings as fertiliser, and protecting the plant from predators. It seems to be a win-win partnership.

Ecosystem importance of sundews

Sundews contribute to their ecosystems by nutrient cycling, as they capture and digest insects and bring the goodness down into the soil. They also help stabilise boggy and sedimentary soils. Although sundew leaves seem unpalatable to animals, the tubers are sometimes a food source for foraging mammals such as bettongs.

Sundews at risk

Sundews are vulnerable to climate change and habitat change, particularly when there is extended drought. If rain doesn’t occur until later in the season, the sundew’s growing period is cut short and it may not have the opportunity to fully mature and optimally reproduce.

Sustaining South Australia’s sundews involves the protection and restoration of habitats like wetlands and woodlands, and global climate action. As part of South Australia’s precious biodiversity, these sticky little wonders are important to preserve for generations to come.

With thanks to:

State Herbarium of South Australia — Prof. Michelle Waycott, Chief Botanist

National Parks & Wildlife Service — Heiri Klein, Conservation Ecologist, Kangaroo Island

- Anthony Abley, Conservation Ecologist, Adelaide & Mount Lofty Ranges